STOP! HAVE YOU READ?

Cockfighting, Facebook, & Virulent Newcastle Disease Series | Part 1

Continue Reading:

Cockfighting, Facebook, & Virulent Newcastle Disease Series | Part 2

Containing an Outbreak in the Age of Social Media

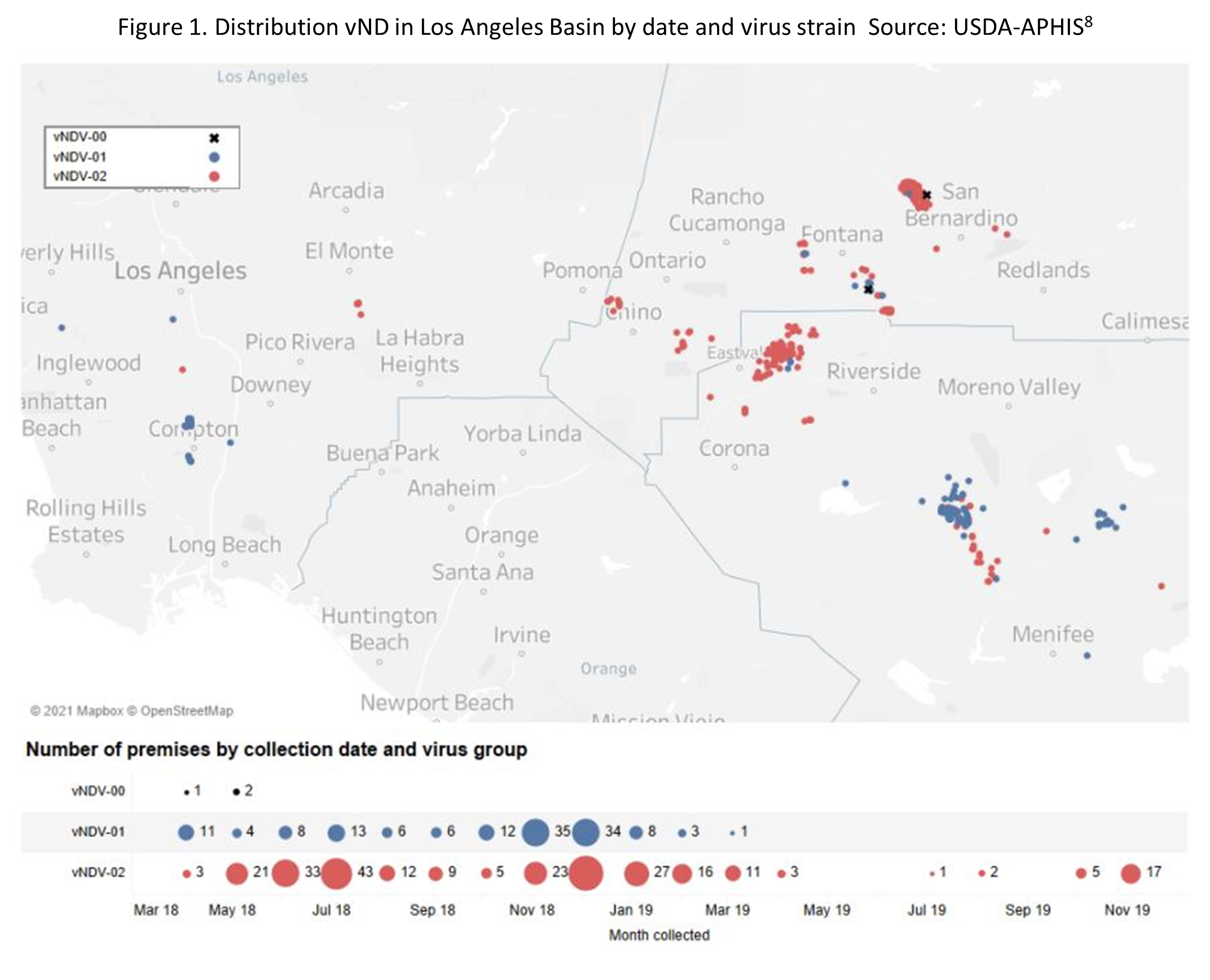

By December 2018, vND had spread extensively in backyard poultry and commercial flocks in the Los Angeles Basin (see figure 1)4,8. It was at this time that vND was first detected in a commercial operation: a pullet ranch in Riverside county. This was soon to be followed by positive diagnoses in roughly half a dozen commercial operations in the vicinity. The emergence of cases in these operations would greatly influence the magnitude of the outbreak, as ~¾ of the 1.2 million birds euthanized were from a handful of commercial operations.

The first of two out-of-state cases was detected in January of 2019 in Utah County, Utah. This case was linked to birds that had been transported from California in violation of quarantine regulations. The infection was detected because a concerned individual contacted the Utah State Veterinarian’s office to report sick and dying birds at the affected premises, which had birds owned by several different individuals. The Utah State Veterinarian contacted the individuals and the premises was depopulated8.

Another out of state case with a genetic link to this outbreak was detected in Coconino County, Arizona in March 2019. The case occurred in a pet chicken on a premises with other chickens. The other chickens were depopulated and no further cases were found in the vicinity8.

To aid in the incident response, the United States Postal Service (USPS) issued an industry alert on March 7th, 2019 indicating that they would no longer allow shipments of poultry into or out of zip codes 90000-93599. This included birds, and hatching/embryonated eggs. This quarantine was in effect until June 1st, 20208. Postal and parcel services also assisted the response by delivering test kits to poultry owners so that responders wouldn’t have to risk spreading the virus from farm to farm by doing the tests themselves12.

In April of 2019, a retired police officer and backyard poultry enthusiast that lived close to an affected commercial poultry operation was informed by the CDFA that her birds would be euthanized, despite none of them having developed clinical signs or testing positive. The birds in her backyard operation were considered to be pets by her family, and she claimed that she had done everything she had been asked to do by CDFA theretofore, and was very upset with the depopulation order. She was so upset in fact, that she live streamed the depopulation event and started a Facebook group called ‘Save our Birds’ (SOB) that would go on to organize protests at the premises of other backyard flock owners whose birds were slated for depopulation. Her initial video garnered over 225,000 views, and the group’s activities became a major hinderance to operations crews from the incident response. Furthermore, she used her platform to encourage people to run and hide with their birds, essentially breaking the quarantine that had been in place around the area. It is unclear at this point what effect these activities had on the course of the outbreak aside from being a nuisance/hazard to the response teams. However, the SOB group did raise enough money to file a lawsuit against CDFA and Dr. Annette Jones. SOB was not the only social media group formed by members of the poultry community. Another social media group known as ‘End Virulent Newcastle Disease’ was started a few days after SOB as a counterweight, but it garnered a fraction of the followers of SOB11.

For its part, the unified command worked actively throughout the outbreak to conduct outreach to the public at retail feed stores and other venues where poultry owners might congregate. However, it was slow at first to leverage social media for public outreach. During the 2002 outbreak, the CDFA relied heavily on news media to get its message out. The nation was still reeling from 9/11, and events like the outbreak of a foreign animal disease seemed to attract the public’s interest. It may be too, that the overall mood of the nation was more conducive to cooperating with state and federal authorities. That outbreak occurred before the war in Iraq, The Great Recession, or the rise of social media and mass political polarization. However, this most recent outbreak occurred at a time when political headlines and mistrust in public institutions dominated the 24-hour news cycle. The media were less interested in a somewhat isolated outbreak of an obscure chicken virus, and some members of the public were less inclined to cooperate with containment efforts. As such, CDFA had to learn how to adapt to public information in the age of social media. It took a while to get up and running, but they eventually hired a PR firm and would come to rely heavily on social platforms for messaging10,12.

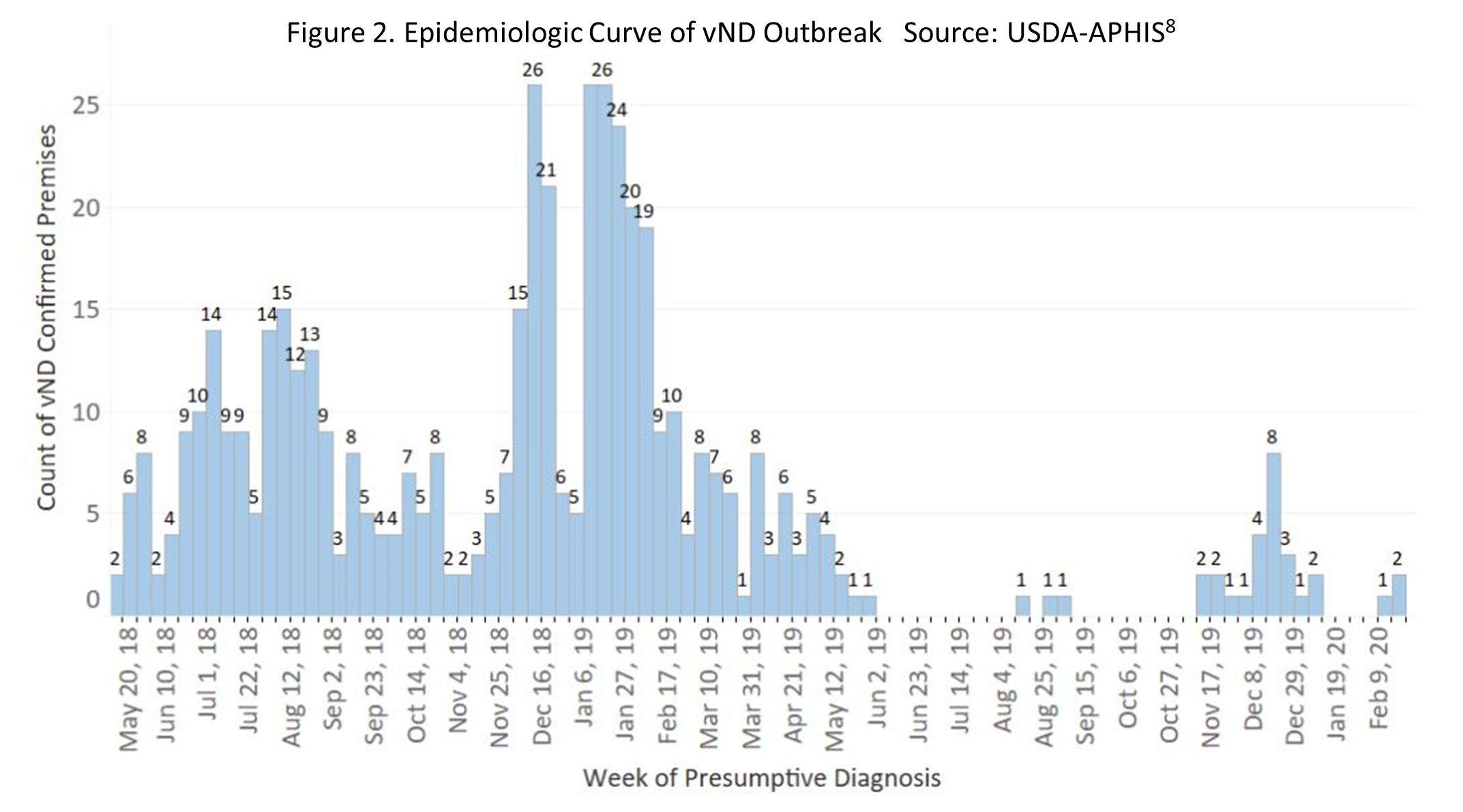

This dynamic would seem to be a harbinger for what was to come in the near future. Much of the rhetoric used by the SOB Facebook group closely mimicked that of groups opposed to public health measures instituted during the COVID-19 pandemic. For many of the producers affected by vND, it was difficult to conceptualize the threat, as many of the chickens euthanized were not sick and had tested negative, much like for many people COVID-19 did not represent a threat that was much more significant than a nasty cold. For individuals trained in disease outbreak response, the rationale behind these controversial tactics is fairly evident, but for those who are not, it can be pretty hard to ‘trust the science’. The bulk of cases and depopulation events occurred over a year long period from May 2018 to approximately the 1st of June 2019, with the highest peaks occurring in the winter. It’s feasible that the outbreak may have been contained within roughly a year’s timeframe, however a group of exhibition birds began spreading the virus in November of 2019 (see Figure 2). These birds were involved in prohibited exhibition activities (e.g. cockfighting) which likely contributed to the presence of the virus going undetected for so many months then emerging rapidly as the frequency of these underground events increased in the last quarter of the year (the cockfighting season begins in late November as the birds fight better in the winter)8,13.

Continued in Cockfighting, Facebook, & Virulent Newcastle Disease Series | Part 3

Sources:

-

Newcastle Disease in Poultry. Merck Veterinary Manual. Patti J. Miller. 2016. https://www.merckvetmanual.com/poultry/newcastle-disease-and-other-paramyxovirus-infections/newcastle-disease-in-poultry?query=virulent%20newcastle%20disease

-

Chapter 59. Medical Microbiology 4th edition. 1996 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8461/

-

Newcastle Disease Standard Operating Procedures: 1. Overview of Etiology and Ecology. United States Department of Agriculture. 2013. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/emergency_management/downloads/sop/sop_nd_e-e.pdf

-

Virulent Newcastle Disease. California Department of Agriculture. 2022. https://www.cdfa.ca.gov/ahfss/Animal_Health/Newcastle_Disease_Info.html#:~:text=1971%20Exotic%20Newcastle%20Disease%20Outbreak,12%20million%20birds%20were%20destroyed

-

Virulent Newcastle Disease (vND). Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 2021. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/avian/virulent-newcastle/vnd

-

Poultry – Production and Value 2021 Summary. National Agricultural Statistics Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 2022. https://www.uspoultry.org/economic-data/docs/broiler-production-and-value-2021.pdf

-

S. Dairy, Livestock and Poultry Exports in 2021. Foreign Agricultural Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 2022. https://www.fas.usda.gov/commodities/dairy-livestock-and-poultry

-

Epidemiologic Analyses of Virulent Newcastle Disease in Poultry in California. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 2021. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/downloads/animal_diseases/ai/epi-analy-vnd-poultry-calif.pdf

-

Cockfighting Laws. National Conference of State Legislatures. Jonathan Griffin. 2014. https://www.ncsl.org/research/agriculture-and-rural-development/cockfighting-laws.aspx#:~:text=State%20Action,and%20the%20U.S.%20Virgin%20Islands

-

Personal Communication with CDFA. 2022.

-

To stop a virus, California has euthanized more than 1.2 million birds. Is it reckless or necessary? Los Angeles Times. Jaclyn Cosgrove. 2019. https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-virulent-newcastle-disease-outbreak-in-southern-california-20190607-story.html

-

California’s Defeat of Newcastle Disease Offers Lessons for Poultry Industry. Lancaster Farming. Philip Gruber. 2021. https://www.lancasterfarming.com/news/main_edition/california-s-defeat-of-newcastle-disease-offers-lessons-for-poultry-industry/article_20c2a0a8-157b-11ec-9945-3b2d61b62862.html

-

History they don’t teach you: A tradition of cockfighting. White River Valley Historical Quarterly. Lynn Morrow. 1995. https://thelibrary.org/lochist/periodicals/wrv/v35/n2/f95d.htm